Table of Contents

Government policies and interventions for development in various sectors and issues arising out of their design and implementation

This article deals with ‘Government policies and interventions for development in various sectors and issues arising out of their design and implementation.’ This is part of our series on ‘Governance’ which is important pillar of GS-2 syllabus . For more articles , you can click here.

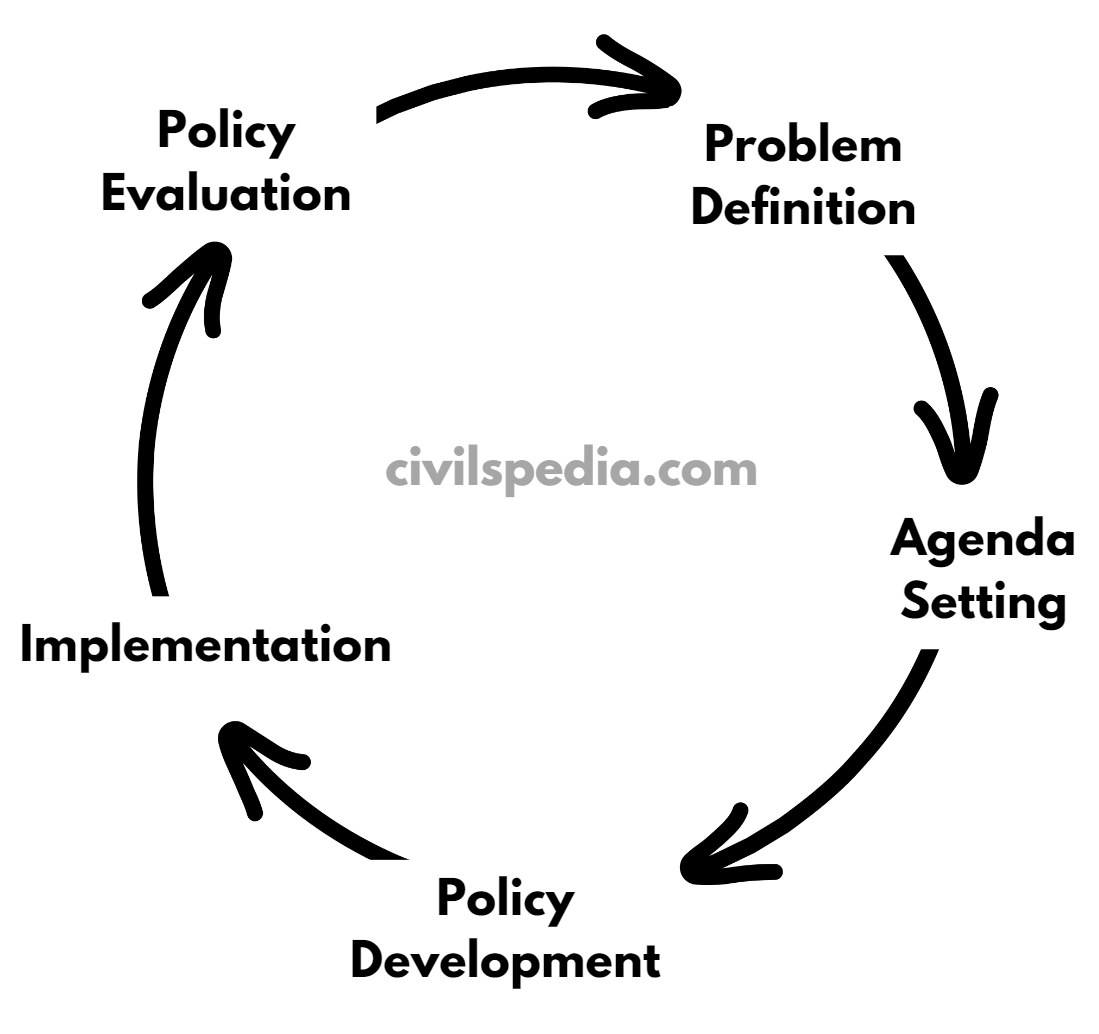

How is Policy Made?

Policy Making involves various stages

- Problem Definition: In this stage, policymakers identify and define a particular issue or problem that requires attention and action from the government.

- Agenda Setting: Once a problem has been defined, it should be placed on the political agenda for consideration and action. Agenda setting involves determining which issues receive attention and priority from policymakers. This stage often involves debates, lobbying, advocacy efforts, and the formulation of policy proposals.

- Policy Development: In this stage, policymakers and relevant stakeholders work together to formulate potential policy solutions or approaches to address the identified problem.

- Implementation: Once a policy has been developed, it needs to be put into action. Implementation involves the actual execution of the policy, including the allocation of resources, the establishment of procedures and guidelines, the coordination of various stakeholders, and the enforcement of regulations.

- Policy Evaluation: After a policy has been implemented, evaluating its effectiveness and impact is essential. Evaluation can involve collecting and analyzing data, conducting research, measuring key indicators, and soliciting feedback from stakeholders and affected communities. The findings from policy evaluation provide valuable insights for policymakers to determine if adjustments, modifications, or alternative approaches are necessary to improve the policy or address any shortcomings.

Different Types of Policy Implementations

Policy implementation is the fourth stage of the Policy cycle in which adopted policies are put into effect.

Different Types of Policy Implementation

Policy Implementation 1.0

- It is the ability to deliver a standard product or carry out a standard procedure across the country.

- It can work well when one size fits all— the same dose of the same polio vaccine, the same procedure for voting, the same identity card etc.

- India has already proved its mettle in this area. For example – conducting the world’s largest election, ADHAAR project, 100% coverage of UIP (Universal Immunization Program), etc.

Policy Implementation 2.0

- In addition to carrying out the standard procedure, it also entails a change in behaviour. This policy implementation depends not solely on administrative actions but also on fostering behavioural change among the target population.

- The best example is the Swachh Bharat Abhiyan (Clean India Campaign). Here, the challenge was not limited to the construction of toilets and infrastructure; it also required a fundamental shift in societal norms and individual behaviours related to sanitation.

Policy Implementation 3.0

- It requires coherence amongst many policies, coordination among many agencies, and cooperation of many stakeholders. The successful execution of a policy often relies on its alignment and integration with other related policies to ensure a comprehensive and harmonized approach to addressing societal challenges.

- For example, the Industrial Policy of 1991 requires Policy 3.0 competencies. Implementing the Industrial Policy of 1991 necessitated a comprehensive approach that considered the interconnectedness of various policies, ensuring their compatibility and coherence to drive economic growth and development.

Why is there bad policy formulation, design & implementation?

Excessive fragmentation in thinking and action

When multiple departments or ministries are responsible for addressing different aspects of a particular sector, it can lead to challenges such as lack of coordination, conflicting objectives, and duplication of efforts. For example,

- Five departments/Ministries in India deal with the transport sector, whereas in the US and UK, it is a part of one department.

- Environmental protection in India involves multiple ministries and departments, including the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, the Ministry of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation, and the Ministry of Power.

Excessive Overlap between Policymaking and Implementation

- Those who formulate are themselves involved in implementation. Hence status-quo or a minimum amount of changes are presented in the new policy. E.g., In the education sector, policymakers who formulate education policies often include officials from the Ministry of Education and other relevant government bodies. However, these policymakers are also responsible for implementing the policies they create. This overlap can result in limited innovation and transformative changes in the education system.

Lack of Non-governmental Inputs and Informed Debates

- In India, policymakers exclude or marginalize inputs from non-governmental actors, such as NGOs and civil society organizations. Hence, the resulting policies may fail to adequately address the needs, perspectives, and concerns of the affected communities. For example, in the formulation of public health programs, the exclusion of NGOs working with marginalized communities can result in policies that inadequately address their specific health challenges.

Lack of Evidence-based Research

In India, the policies are often developed without a robust foundation of empirical data, analysis, and research, leading to suboptimal outcomes. E.g.,

- Implementing the National Health Insurance Scheme (Ayushman Bharat) faced challenges due to a lack of evidence-based research. While the intent was to provide health coverage to economically vulnerable populations, the design and implementation of the scheme encountered issues related to inadequate infrastructure, limited healthcare provider networks, and low awareness among beneficiaries. Insufficient research on existing healthcare systems, demand patterns, and cost projections hindered the effectiveness of policy implementation and limited the scheme’s impact.

Politically Motivated policies

Politically motivated policies can lead to inadequate policy formulation, flawed design, and suboptimal implementation in India. These policies are driven primarily by political considerations, such as electoral gains or appeasing specific interest groups, rather than being based on sound evidence, expert advice, or the long-term welfare of the nation. E.g.,

- Agriculture Sector: The introduction of populist measures like loan waivers and high minimum support prices (MSP) for crops, without considering market dynamics or fiscal sustainability, can distort market forces, create inefficiencies, and burden the government finances.

- Education Sector: The introduction of reservation quotas in educational institutions based solely on political calculations rather than the principles of merit and equal opportunity can undermine the quality of education and compromise the overall academic environment.

- Infrastructure Sector: Projects driven by electoral considerations rather than economic viability can result in poor planning, cost overruns, delays, and inadequate infrastructure quality.

Centralized Policy Making

Centralized policy making, which follows a one-size-fits-all approach, can lead to challenges in policy formulation, design, and implementation in India. This approach overlooks the diversity of contexts, needs, and challenges across the country’s different regions, sectors, and communities. E.g.,

- A uniform Minimum Support Price (MSP) for crops across the country does not account for variations in production costs, market dynamics, and local demands, leading to unequal benefits and discontent among farmers.

- Centralized educational policies, such as uniform curriculum frameworks or standardized assessments, may not align with the specific needs and aspirations of students and communities in different states or regions.

Insufficient Capacity and Expertise

Effective policy formulation and implementation require skilled personnel, adequate resources, and institutional capacity. Limited technical expertise and a lack of capacity-building initiatives can impede the implementation of policies. For example

- Implementing the Continuous and Comprehensive Evaluation (CCE) system in schools faced challenges due to a lack of trained teachers, resulting in inconsistent implementation and ambiguity in assessment practices.

- Implementation of Crop Insurance Schemes has faced difficulties due to limited awareness among farmers, inadequate risk assessment capabilities, and challenges in timely claim settlements.

- Implementation of pollution control measures in industrial sectors has been hampered by limited expertise in monitoring and enforcement.

Complex Procedures

- Complex procedures in policy implementation can hinder the participation of individuals, especially those from disadvantaged backgrounds.

- According to a World Bank report, when schemes are designed with intricate procedures that require poor individuals to visit offices, fill out forms, and navigate complex rules, their participation decreases significantly, often to as low as 10%. However, when these schemes are revamped and local officials, such as Asha workers or postmen, go door-to-door to implement them, participation increases substantially, reaching as high as 70%.

Fear of Unknown

- The fear of the unknown, particularly prevalent among individuals with limited resources, can contribute to challenges in policy formulation, design, and implementation in India. This fear stems from the constant worry about potential financial loss and the inability to absorb setbacks.

- Due to their precarious financial situations, individuals with limited resources may prioritize immediate gratification over long-term investment. Individuals with limited resources may not show significant interest in schemes designed to promote financial inclusion. Despite the potential long-term benefits of financial inclusion, immediate concerns and the need for immediate gratification take precedence for these individuals.

- Programs focused on skill development and vocational training may struggle to attract individuals from economically disadvantaged backgrounds. The fear of investing time and resources in acquiring new skills without a guaranteed immediate return on investment can discourage participation, hindering the effectiveness of such initiatives.

- Addressing the fear of the unknown and aligning policies with immediate needs and concerns can contribute to better policy formulation, design, and implementation in sectors aiming to uplift the economically disadvantaged population.

Social Dynamics and Obligations

Policies must be formulated and implemented while keeping in mind the social dynamics and obligations that influence the behaviour and decision-making of the poor. When policies are formulated, designed, and implemented without considering these factors, they might not work. E.g.,

- In rural India, where agriculture is a predominant occupation, poor farmers often face pressures to conform to social expectations. It can influence their cropping decisions and practices. For instance, if a farmer chooses to cultivate a crop that differs from what their neighbours or relatives cultivate, they may face the risk of crop theft or vandalism.

- Microfinance plays a crucial role in providing financial services to the poor, especially in rural India. However, some poor individuals may take microfinance loans not necessarily because of their dire need for cash but to signal their relatives and neighbours that they do not have spare money. This stems from the social obligation to help others in times of need, even if it means taking on debt. If policymakers fail to recognize this underlying motivation, it can lead to misinterpretation of the actual financial needs of the poor and the effectiveness of microfinance interventions.

How to Address these issues?

- Enhanced Interdepartmental Coordination: Establish mechanisms and platforms for improved coordination and communication among the relevant departments and ministries. This can include regular meetings, joint task forces, and the sharing of information and resources.

- Stakeholder Engagement and Consultation: Involve relevant stakeholders, such as civil society organizations, industry representatives, and affected communities, in the policymaking and implementation processes. Their perspectives and expertise can contribute to more comprehensive and balanced decision-making.

- Separation of Roles: One approach is to establish a clear separation between policymakers and implementers. Policymakers should primarily focus on formulating effective and innovative policies, while implementers should be responsible for executing those policies.

- Enhancing Stakeholder Engagement: Policymakers should actively engage and involve non-governmental actors, including NGOs and civil society organizations, in the policymaking process. This can be achieved through regular consultations, open dialogues, and structured platforms for meaningful participation.

- Strengthen Research Infrastructure: Invest in building robust research infrastructure, including research institutions, think tanks, and universities, equipped with the necessary resources, expertise, and technology to conduct empirical studies. This will facilitate the generation of reliable data and evidence to inform policy decisions.

- Decentralization and Regional Autonomy: Introducing decentralization in policymaking allows for greater regional autonomy and decision-making power at the local or state level. This enables policies to be tailored to the specific needs, contexts, and challenges of different regions.

- Enhance Training and Capacity Building: Implement training programs and capacity-building initiatives to equip personnel involved in policy implementation with the necessary skills and knowledge. This could involve conducting workshops, seminars, and specialized training sessions to enhance technical expertise and understanding of policy objectives.

- Simplify Procedures: This can include reducing paperwork, eliminating unnecessary bureaucratic steps, and streamlining the application process. By making procedures more straightforward and user-friendly, individuals are more likely to participate.

- Societal Understanding: Policymakers need to develop a comprehensive understanding of the social dynamics and cultural norms that shape the behaviour and decision-making of the target population. It requires conducting thorough research, engaging with local communities, and consulting experts or social scientists who possess knowledge of the specific context. By gaining insights into the social pressures, expectations, and obligations faced by the poor, policymakers can design policies that align with these realities.