Table of Contents

Inter-State River Water Disputes

This article deals with ‘Inter-State River Water Disputes – Indian Polity.’ This is part of our series on ‘Polity’ which is important pillar of GS-2 syllabus. For more articles , you can click here

Constitutional Provisions

Status of Water in the Constitution

| State List | Entry 17: Water, that is to say, water supplies, irrigation & canals, etc., subject to provisions of Entry 56 of List 1 |

| Union List | Entry 56: Regulation and Development of Inter-State Rivers & River Valleys |

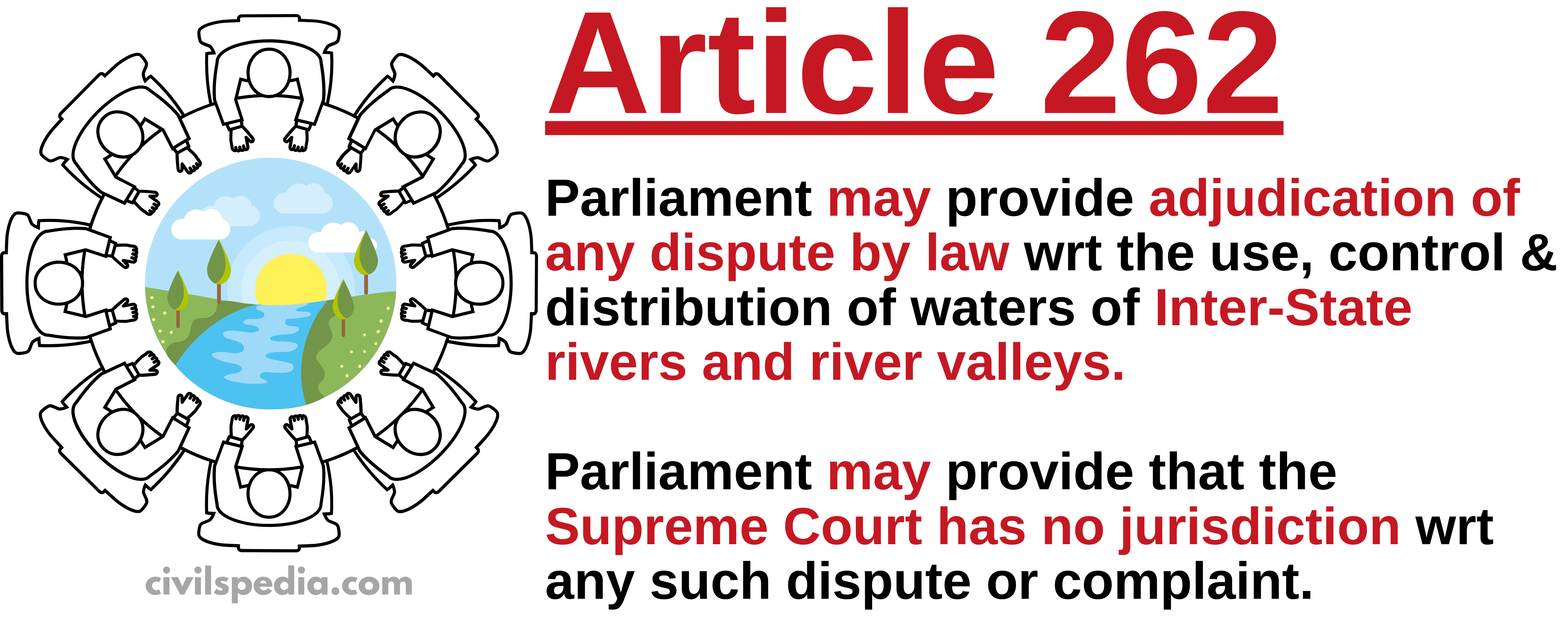

When a water dispute arises between two states, Article 262 is invoked & in pursuance of Article 262, two Acts were passed by the Parliament.

River Boards Act,1956

The Act is designed to regulate and facilitate the development of inter-state rivers to ensure effective water resource management. The key features of the River Boards Act 1956 are

- Establishment of River Boards: These boards are instrumental in coordinating efforts to regulate and develop rivers that flow through multiple states.

- Board Establishment on State Government Request: River Boards are not unilaterally imposed but are established based on requests from State Governments.

Inter-State River Water Disputes Act,1956

The Inter-State River Water Disputes Act of 1956 provides a mechanism for resolving disputes related to the sharing of river waters between different states in India.

- Initiation of Tribunal: If a Riparian State believes that its interests are adversely affected by the actions or plans of another state, it can request the government of India to establish a Tribunal to address the dispute.

- Timeline for Tribunal Setup: The government of India is mandated to set up the Tribunal within one year of receiving such a request.

- Composition of Tribunal: The Tribunal comprises three members, each of whom must be a Judge of either the Supreme Court or a High Court.

- Final and Binding Decision: The decision rendered by the Tribunal holds ultimate authority and is deemed final and binding. The Supreme Court or any other court don’t have any jurisdiction in this regard.

A total (9) such tribunals have been established till date. Important ones are

- Ravi & Beas: Involving Punjab and Haryana, formed in 1986 and still pending the award.

- Kaveri: Involving Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Kerala & Pondicherry, with time period 1990-2007

- Mahanadi: The most recent tribunal, formed in 2018, involving the states of Odisha and Chhattisgarh.

Causes of these Disputes

- Agriculture and Water Scarcity: Riparian states depend on river water for agriculture. Such issues intensify during low rainfall seasons. Examples include disputes over the Kaveri, Krishna, Ravi, and Beas rivers, primarily revolving around sharing water for agricultural purposes.

- Multipurpose Projects and Dams: Conflicts often arise between upstream and downstream states regarding multipurpose projects and dams. The Mahanadi issue serves as an illustration of such disputes.

- River Joining: It is usually done to divert river water from sufficient to deficient river basins, but many issues arise, such as environmental assessment, submergence of surrounding lands, etc. Mahadayi/ Mandovi (Goa vs Karnataka) is an example of such a dispute.

- Unborn States Share: Disputes arise when a tribunal’s judgment on a contested river involves states that later undergo division or creation. The Krishna water tribunal is an example where the parties were Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra, and Karnataka. But as the new state Telangana has come into being, it approached the Supreme Court for its right to get a proper share.

Why Tribunals for Inter-State Water Disputes?

Article 262 of the Constitution lays down that the Parliament may by law provide for the adjudication of any dispute with respect to any Inter-State River (ISR). Accordingly, the Parliament enacted the Inter-State River Water Dispute Act 1956, which provides for the reference of such a dispute to a Water Tribunal. The said Act bars the Supreme Court or any other Court from exercising jurisdiction in respect of any water dispute.

The main reasons for keeping River Disputes out of the purview of the court’s jurisdiction were that (the whole of the Constituent Assembly agreed that there is a need for Tribunals to settle Inter-State River Disputes (but there wasn’t unanimity on Permanent Tribunal or Temporary Tribunals)) :

- Speedy Disposal: The Act ensures the swift resolution of Inter-State River water disputes by making the tribunal’s decision final and binding, thereby avoiding prolonged legal processes.

- Technical and Scientific Expertise: Since the resolution of Inter-State River disputes hinges upon heaps of technical and scientific data, the resolution of such disputes by specialized tribunals would allow for a better appreciation of such data.

- Flexible and Informal Proceedings: Unlike courts bound by strict legal procedures, tribunal proceedings are relatively informal. This flexibility allows for deliberative decision-making and discretionary measures, fostering the potential for mutually negotiated settlements.

In this context, it can be argued that the rationale behind excluding the jurisdiction of courts was fairly well-intentioned.

Main Problems with Present System and Remedies

The problem lies elsewhere and has been well documented by many commissions, including the Sarkaria Commission. These include:

- Long delays & uncertain time frame: The existing system is plagued by prolonged delays, leading to uncertainty. For example, in the Ravi Beas case, referred to the Tribunal in 1986, the matter is still pending.

- Issue of finality: The Tribunal acts as the arbiter for water disputes between states. Although courts are barred from interfering, matters are still taken to courts through Special Leave Petitions. E.g., the Cauvery Case, where the matter was brought to courts through Special Leave Petitions.

- Enforcement Issues: Inadequate provisions for enforcing Tribunal awards lead to challenges in implementation. There is political resistance and reluctance from states to comply with Tribunal awards due to political considerations.

- Politicization of Water Issues: Even after the award is announced, in times of coalition politics, sometimes the centre doesn’t publish it in the gazette.

Suggestions to improve this

- Institutional Changes: Utilize the Inter-State Council as a platform for resolving water conflicts effectively.

- Permanent Tribunal: Advocate the establishment of a Permanent Tribunal, a concept supported by Ambedkar during Constitutional Assembly Debates.

- Mediation Approach: Reform the current adversarial

judicial process to mediation for a mutually acceptable resolution.

Mediation has solved a large number of River Disputes, even at the

international level. For example,

- World Bank played the role of mediator between India and Pakistan in the Indus Treaty.

- The Vatican became a mediator in solving the Zambezi River dispute involving eleven countries.

- Declaring Rivers National Property: The establishment of separate corporations on the pattern of the Damodar Valley Corporation may be immensely useful in this direction.

- Bringing Water to Concurrent List: As suggested by the Ashok Chawla Committee, water resources should be included in the concurrent list for better coordination and management.

Proposed Changes in Inter State River Water Disputes Act

The following changes have been proposed in the Inter-State River Water Disputes Act of 1956 to resolve the deficiencies the present mechanism faces.

Single Permanent Tribunal

- Establish a single, Permanent Tribunal for adjudicating all inter-state river water disputes.

- Awards will be notified automatically.

- Composition of the Tribunal: Chairperson, Vice-Chairperson, and not more than six other Members

- Members from both judicial (3) and technical backgrounds (3).

- Even in Constituent Assembly debates, the setting of the Permanent Tribunal to resolve Inter-State River Water Disputes was greatly favoured, and BR Ambedkar was in favour of the Permanent Commission. The act favouring the Temporary Commission was favoured on the basis of experience that such issues would not come up. This is not the case now, and such disputes are rising very frequently.

Dispute Resolution Committee (DRC)

- DRC will handle disputes prior to the tribunal, with a resolution timeline of one year.

- Most disputes will get resolved at the DRC’s level itself. But if the state is not satisfied, it can approach the tribunal.

Data Agency

- Establish an agency to collect and maintain updated water data in each river basin in the country.

- The collected data will aid in the timely resolution of water disputes

Timeline

- The Tribunal must give a decision within two years, with a possible extension of one more year.

- The decision of the Tribunal shall be final and binding.

Case Study: Cauvery Issue

| 1924 | The agreement was signed between Madras Presidency and Mysore to build a dam in Mysore. The agreement was valid for 50 years, and it led to the construction of the Krishnaraja Sagar Dam. Note: The agreement was heavily in favour of the Madras Presidency. Mysore was allowed to construct just one dam. |

| 1960s | Karnataka wanted to make more dams on Cauvery, but Tamil Nadu didn’t allow it on the basis of the 1924 Agreement. |

| 1974 | The Water Sharing Agreement lapsed after 50 years. Karnataka decided to go ahead with making dams. 4 dams were made by Karnataka in quick succession. |

| 1986 | Tamil Nadu approached the Centre for setting up a Tribunal |

| 2 June 1990 | The Cauvery Water Dispute Tribunal (CWDT), headed by Justice Chittosh Mookerjee, was set after the Supreme Court’s direction. |

| 2007 | CWDT issued its final order, allocating water shares (in tmcft): – Tamil Nadu: 419 – Karnataka: 270 (Karnataka claimed 312, but CWDT considered earlier agreements) – Kerala: 30 – Puducherry: 7 Karnataka and Tamil Nadu contested the order in the Supreme Court via Special Leave Petitions (SLPs). It also recommended the establishment of a Cauvery Management Board. But it was just a recommendation. |

| 2013 | 2013 was a drought year. Tamil Nadu moves Supreme Court seeking directions to Water Ministry for Constitution of Cauvery Management Board as Karnataka wasn’t following orders of CWDT. |

| 2016 | The year 2016 was a drought year, with Karnataka not releasing adequate water. Tamil Nadu went to the Supreme Court again. SC ordered the formation of the Cauvery Water Management Board. |

Point to Note – The main issue in this case (& other River Disputes, too) is a shortage of water. Whenever there are drought-like conditions, states start to fight over the division of Rivers.